One of the exercises career coaches suggest for figuring out what kind of employment to pursue is to list things that you liked doing when you were younger. The fact that I played clarinet pretty intensely, or that I spent about twelve hours (or more) per week at the dance studio, don’t seem particularly helpful in this sort of endeavor. However, two events recently reminded me of something I had sort of forgotten that I loved to do: tell stories.

-

I’ve been spending a lot of time on Etsy lately, hoping to find some clever feminist swag made by creative female artisans. I came across the shop Dead Feminists, which sells letterpress prints of images inspired by quotes from feminist icons. Among them, I saw a print with Japanese iconography and clicked through – it was a picture inspired by a quote from Sadako Sasaki: “I will write peace on your wings and you will fly all over the world."

PEACE UNFOLDS oversized postcard from Dead Feminists on Etsy.

When I was in first grade, I had an extraordinary teacher. I was quiet and awkward, and I didn’t like being around kids my age. I wanted to spend my time with adults and books. I think this teacher understood that clearly. In her classroom, which was plastered floor to ceiling with all of our artwork and colorful bulletin boards, there was a corner in the back dedicated to story time. Almost every day, she would adjourn us to the carpeted floors of the story corner, and she would read us chapters of books—including Eleanor Coerr’s Sadako and the Thousand Paper Cranes. By the time she chose Sadako, I had already read it a number of times, and it had become a favorite. I was so excited that I would get to spend part of school time listening to something that I already loved; it was a comfort among all the other trials of the first grade classroom.

But then my teacher became sick—so sick that she couldn’t talk. So sick that now, as an adult, I admire her more for toughing that day out, for holding on to the idea that she owed us her presence, perhaps to finish that last bit of the story. Yet because she couldn’t talk, she couldn’t finish reading Sadako to us. Then, she asked me if I would be willing to read that day’s portion to the class. I did. Making sure that the other kids knew the rest of the story was more important to me than any anxiety I might have had about speaking in front of a room full of people that already made me uneasy.

-

Lately, my mom has been sorting out old papers. This is no easy task. Both of us keep too many things that we shouldn’t. The last time I was home to visit, she pointed to some papers that she had left out on the table and said, “So uhh, do you want me to keep your novel?” (Never underestimate my mother’s gift for sarcasm.)

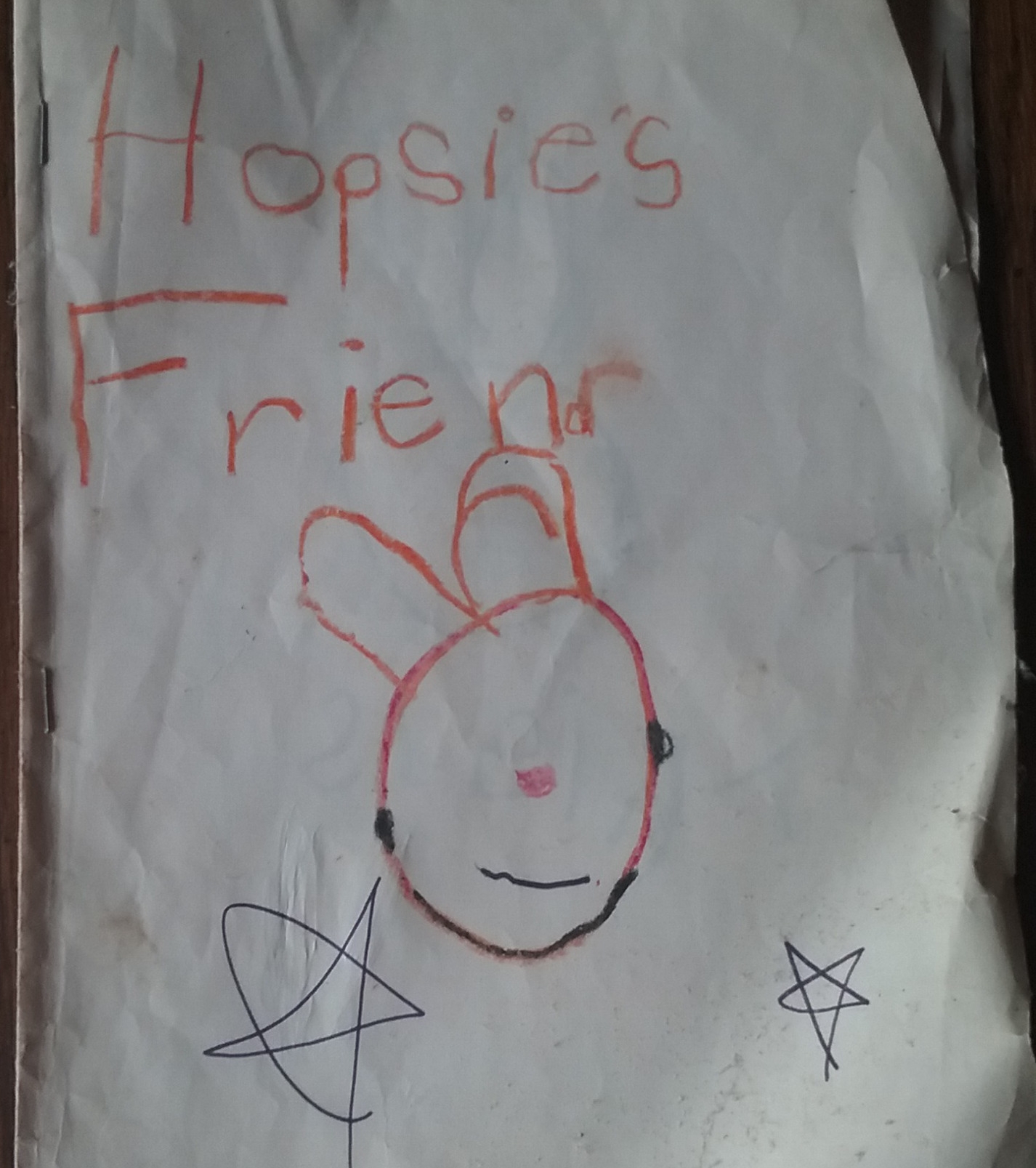

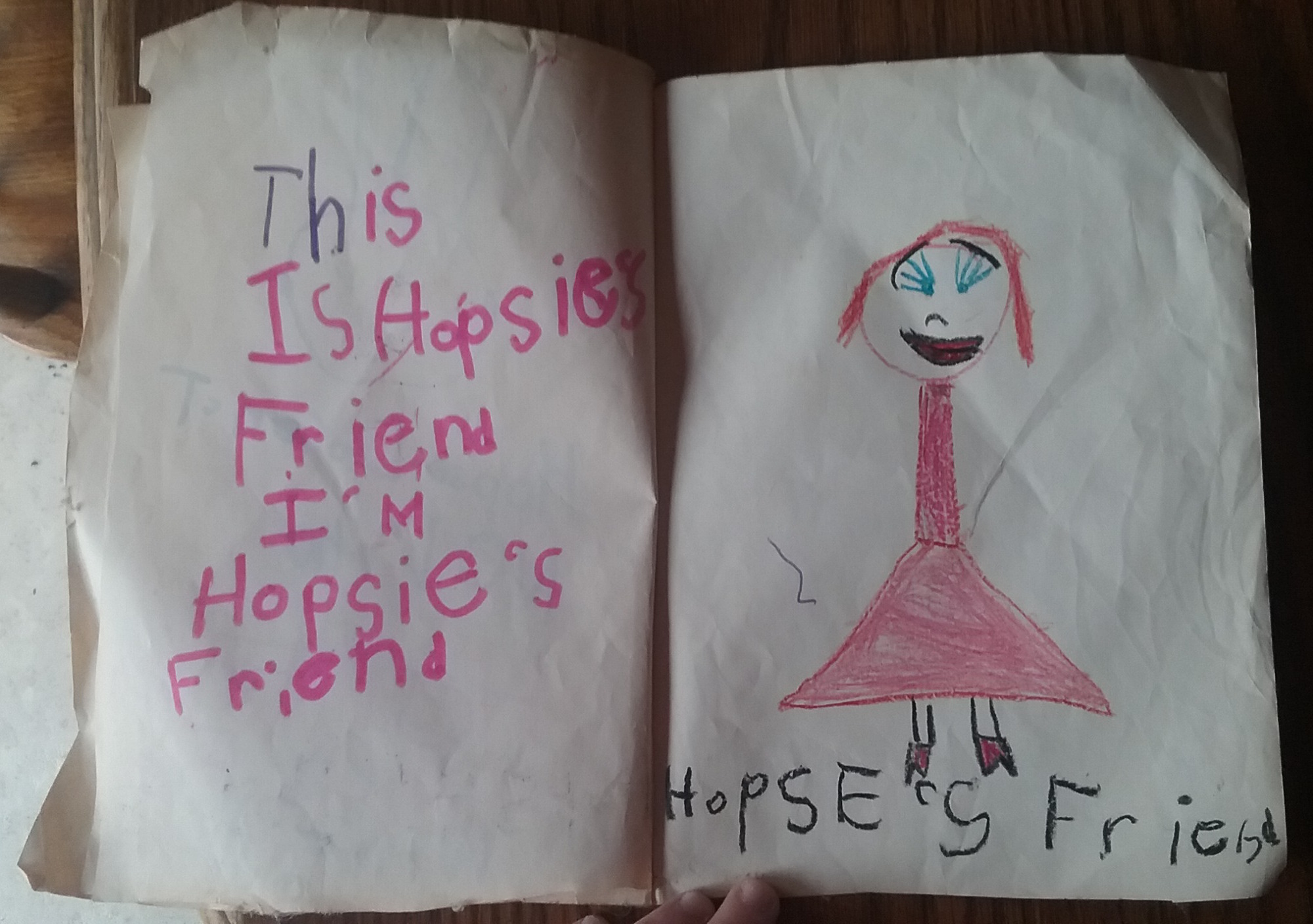

It was hardly a novel, but was actually four or five large sheets of white paper stapled together as a book. On the cover it said Hopsie’s Friend above an illustration of an eyeless bunny, drawn in orange crayon. As I flipped through, I discovered that Hopsie, the rabbit, is unsure if she has any real friends or who might be available to become her friend. As the end, the big reveal is that I am Hopsie’s real friend. It is accompanied by a self-portrait that falls just short of Picasso-level abstraction.

At five or six years old, I used to write these little books all the time. All the time, truly. I felt like I was a never-ending river of stories, that I could write forever and never run out of ideas to share. I’m sure they were all relatively silly stories about bunnies and similar Disney-fied things, but I’m also sure that I was deadly serious about my craft. And that teacher, who I adored, would let me read them out loud to the class during story time as if they were professional finished products. That was how she knew reading Sadako out loud would be a breeze for me, and perhaps she thought that helping me share my work would make me more confident about producing it.

-

I don’t think I’ve written any fiction since another teacher in middle school forced everyone to write a short story as an assignment. Most of the time, I don’t feel that fiction is something I want to write. Academic (art) history was my way of being able to write and to include literary flourishes without the success of the prose depending on them. Sometimes, I sit down and try to write, fiction or nonfiction, even silly listicles (MY top 10 Buffy episodes, etc.), and usually fail. Maybe returning to the melancholy bunny is the answer.